Part II: Finding out about the CDT program through Freedom of Information

First Published: Tuesday 6th November 2018

This is the second part of our exploration of EPSRC's CDT Program, where we explore the difficulities in obtaining the information about the CDTs. To see Part 1, click here.EPSRC were strongly opposed to releasing any information about the mid-term review of CDT's. Accordingly, obtaining the CDT performance information was not easy: it was a process that took place over a 14-month period and necessitated the intervention of the Information Commissioner. In some respects, the fact we faced such difficulty is surprising: there is a shift towards openness in science and this is something that EPSRC strongly encourages. Similarly, there is an increased emphasis upon openness in respect of public administration: indeed, the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg has recently found that Freedom of Information can be a human right in certain circumstances.

The story of obtaining the information in this case is important. This is for two reasons. The first is that in highlighting the difficulties, we hope to smooth future requests: as our analysis in Part I shows, there is an arguable need for transparency in respect of funding policy in the sciences. The second is that EPSRC were forced to advance a range of arguments in an attempt to prevent disclosure of the information that we requested, which are worthy of analysis. There are a number of highlights to this story, including:

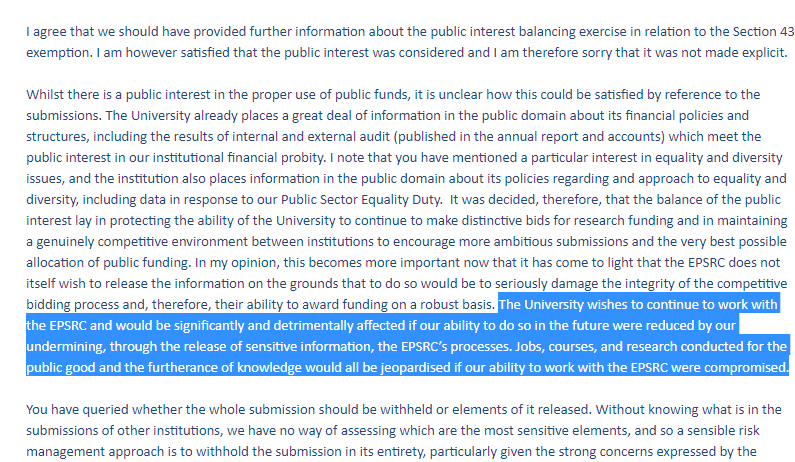

- EPSRC made concerted efforts to prevent universities from disclosing the information requested. A senior manager at one institution informed us that EPSRC would likely reduce their funding if the information was provided and that "jobs, courses, and research conducted for the public good and the furtherance of knowledge would all be jeopardised".

- EPSRC staff made an apparent plan to approach the Information Requester at an event to dissuade him from pursuing his request for information.

- EPSRC argued to the Information Commissioner that some of the senior academics who review proposals cannot be trusted to objectively follow the assessment criteria and instead they would be inappropriately influenced by the 'mid-term' review scores.

- EPSRC has a policy that insofar as CDTs are concerned, poorly performing centres should not be penalised in a fresh-competition and the mid-term review scores (and feedback) were not part of the renewal process.

- Several Higher Education Institutions claimed that a combination of commercial interests (s.43 of the Freedom of Information Act (2000)) and the public interest meant that disclosure would be inappropriate.

The Process for Obtaining the Information

The Freedom of Information Act (2000) provides for a multi-stage process. It is worth outlining certain aspects of this, just so that some of what follows can be put into context.Essentially, anyone ('a requester') can obtain recorded information by making a written request to a public authority (this includes UKRI, Government Departments, and the vast majority of UK universities). If a public authority holds the information, then they must release it to the requester (and in effect, the world), subject to one or more of the provisos within the act. If they refuse the request under one of those provisos either in full or in part, then a requester can ask the public authority again (known as an "internal review"). If the public authority still says "no", then one can complain to the Information Commissioner who can issue a decision notice on that complaint. If either the requester or the public authority is unhappy with the outcome, then they can appeal to the First-tier Tribunal, which is essentially a type of Court who will decide the matter essentially afresh. If the First-tier Tribunal makes an error of law, then it is possible to appeal the decision in question to the Upper Tribunal.

In our case, what broadly happened to the request was this:

- On 15 August 2017, the requester made a written request to EPSRC for what was broadly the scores and feedback of the 2017 CDT Mid-term review exercise.

- EPSRC refused that request on the 11 September 2017 on the asserted application of s.41 (actionable breach of confidence) and s.36 (prejudice to the effective public affairs). The application of s.36 was based upon a "qualified persons opinion" by Professor Phil Nelson, who was their then Chief Executive Officer.

- In response, we applied for an internal review with EPSRC. Because of the nature of the exemptions EPSRC relied upon, we also sent a number of pilot requests to individual Higher Education Institutions (asides in respect of Lancaster University, these were all ultimately refused for commercial reasons).

- The EPSRC refused that internal review request on the 18 October 2017. Accordingly, the requester complained to the Information Commissioner on 23 October 2017. The Commissioner issued her decision notice on the 7th of September 2018. The Commissioner required the EPSRC (now UKRI) to disclose the scores but not the feedback of the 2017 CDT Mid-term review exercise.

- The EPSRC decided not to appeal the Information Commissioner's decision. Accordingly, on the 12th of October 2018 (the deadline set by the Commissioner), EPSRC/UKRI released the scores as required. A short time later, these were also published on EPSRC's website.

EPSRC's interventions

Quiet Encouragement

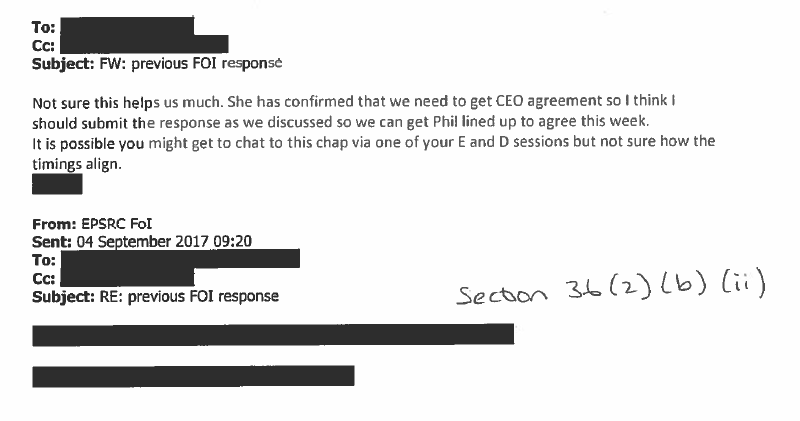

The EPSRC had a rather unusual reaction to the initial request. The contents of their internal discussions amounted to a 70 page document. It appears from those discussions that EPSRC developed a plan to approach the requester at a conference, presumably to persuade him to withdraw their request. If this was not EPSRC's aim, one would have thought they would simply email the requester back as organisations normally do.

In the event that meeting did not happen, as the timings did not in fact "align". However, it is objectively strange for an public body to plan on approaching a requester at an event (especially when their identity is not supposed to be widely circulated in the organisation for reasons of Data Protection legislation).

Running interference

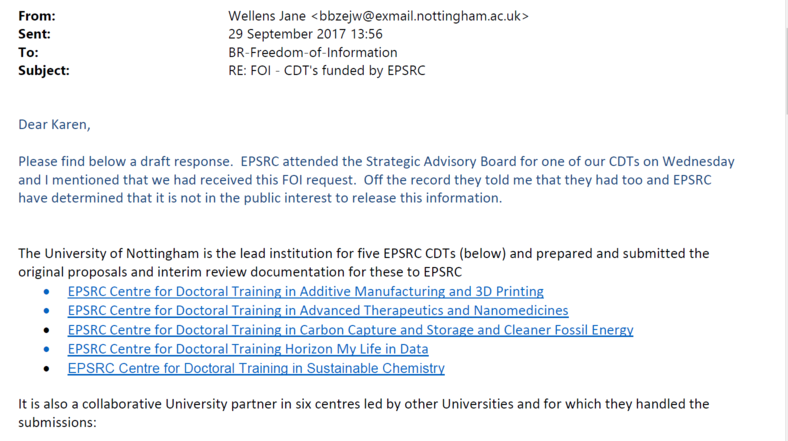

In light of the EPSRC's initial refusal, pilot FOIA requests were made to a number of universities in order to try and obtain disclosure (in this case, we asked for the submissions to the EPSRC, in addition to the feedback EPSRC provided on them). Nearly all of these were refused: the only exemption being Lancaster University (the documents being released in full: namely the report , case studies and EPSRC's feedback). For example, on the apparent advice of EPSRC, the University of Nottingham refused to provide the requested information, claiming that "if this information was in the public domain, it would provide prospective competitors with material that they could use in regard to the 2018 EPSRC CDT call" and therefore there was a "strong public interest in not doing so."

The most concerning example was from a senior manager in a university that performed highly in the CDT league table (so had no reason not to disclose the information). The rationale they raised is rather startling:

To be explicit, this is a senior university manager claiming that EPSRC would likely reduce the funding available to the university in question if any of the information whatsoever was released. The author of that message also made it clear that EPSRC had raised "strong concerns" with the institution in question. Other universities gave somewhat different explanations for refusing to provide the information, but all related to their commercial interests. The University of Bristol claimed that: "Release of the requested information would undermine the University's position in the current competitive review process, and those in the future, where its content would provide our competitors with unwarranted insight into our operations, providing a clear advantage. This would prove detrimental to the chances of desired outcomes, which could in turn negate the future provision of the CDTs and the judicious and best value use of funding by them." Another example is Swansea University, which also asserted that "Disclosing extremely detailed information contained in the submission and specific feedback from the EPSRC would cause commercial harm to Swansea University as this information would provide a competitive advantage to other institutions wishing to put together their own submission". Lancaster University also intially refused to provide the information for commercial reasons, in part on the advice of EPSRC, however this documentation was eventually sent under the Freedom of Information Act (2000) to the requester.

EPSRC's arguments before the Information Commissioner

EPSRC advanced some rather striking arguments before the Information Commissioner. The Senior Case Officer who was then dealing with the case summarised them as follows when sending them to the requester for comment:"As I mentioned, their main line of argument is essentially that disclosure would discourage individual institutions from cooperating with mid-term reviews or else discourage some institutions from applying for funds altogether. Secondly, it explained that everyone who contributes to the peer review process does so under an expectation of confidentiality and if the information was disclosed this would inhibit peer reviewers from providing free and frank feedback or from working with the EPSRC.

In support of this argument the EPSRC has also said that it is concerned that disclosure of information about the performance of their doctoral college could impact on students part way through their studies and have an impact on the employment opportunities of those students who were coming to the final year of their studies."

The Information Commissioner rejected all of those arguments. The Commissioner did not accept that engagement in EPSRC's processes, including the applications for funding and reviewing them was a genuinely voluntary exercise. More fundamentally, at least in respect of the scores themselves, the Commisisoner found that the information itself did not even fit within the terms of the exemptions that the EPSRC relied upon, except in respect of s.36(2)(c) and even then, they did not accept that any harm would come of it. There is however a further argument raised by the EPSRC that would benefit from more analysis:

"Finally, the EPSRC have suggested that disclosure of information on the mid-term reviews could influence peer reviewers when it comes to assessing proposals for new CDTs. It explained that it had already said that scores from mid-term reviews will not be taken into account when assessing new proposals and that information about existing centres (including the outcome of mid-term reviews) will not be made available to peer reviewers. Therefore, it argued that there is a risk that peer review members assessing new proposals would be influenced by the grading given at the mid term review point and that the peer review assessment of these new proposals would not be objective and fair."

This final example is most troubling. EPSRC seem to have made it very clear to the Information Commissioner that they do not trust their esteemed peer reviewers to objectively apply the criteria that they set (whatever that may be), with the result that the process would not be "objective and fair". Indeed, preventing the information from the mid-term review being used in selecting new centres appears to be EPSRC's main concern. As we understand it, Dr Neil Viner (a Director of EPSRC) has more recently written to various University officials and CDT directors, stating that "EPSRC is aware of UKRI Observatory and the article on the CDT mid-term review ... We reiterate the point made in the 2018 call documentation that new and existing centres will be treated equally and as such the mid-term review ratings from the 2013 CDT exercise will not be made available to panel members, by EPSRC, as part of the peer review process for the current call." There are three problems with that. First, this website and our previous blog in particlar has attracted a large volume of traffic, presumably including many of the panelists themselves. Second, it is unclear how it is fair for relatively poorly performing centres (and Universities) to not have this taken into account in the present funding competition: indeed, one must wonder how this could amount to the "effective conduct of public affairs" (one of the exemptions relied upon by the EPSRC under the Freedom of Information Act (2000)). There is a third and more fundamental problem, as illustrated in Lancaster University's submission to the mid-term review, which illustrates the strong advantages that renewals (as opposed new submissions) have, despite EPSRC's claims to the contrary:

"It is still our belief that the underlying cost of offering such a programme is such that, for STOR-i to be sustainable, we will continue to need ongoing research council investment. It is this core funding that enables us to leverage the substantial levels of cash and in-kind contributions across a range of UK business sectors. Based on our track record, and the ever growing demands for highly trained STOR research leaders across all sectors, we can confidently assert that we will continue to leverage substantial industrial and institutional support in the future. Indeed several of our strategic industrial partners are sufficiently concerned about STOR-i's long-term viability that they have already indicated to us that they will offer substantial support to our activities to ensure the renewal of the CDT."

Perhaps unsurprisingly then, this particular batch of arguments from the EPSRC were not accepted by the Commissioner and the scores were ultimately provided. However, the Commissioner decided on the basis of a further argument advanced by the EPSRC not to provide the feedback. This argument was that it would undermine the very running of existing centres, by way of "undue scrutiny": this (new) argument was accepted without being put to the information requester. So for now, we do not have the written feedback, which somewhat limits the analysis that can be done. However, what we do know is that whatever is contained in that feedback is highly critical of certain centres who were given relatively low scores: after all, that was the reason the Commissioner gave for allowing EPSRC to withold it.